preferences < people

on certainty, closeness, finding space within relationships, and the grief inherent in love. ✷

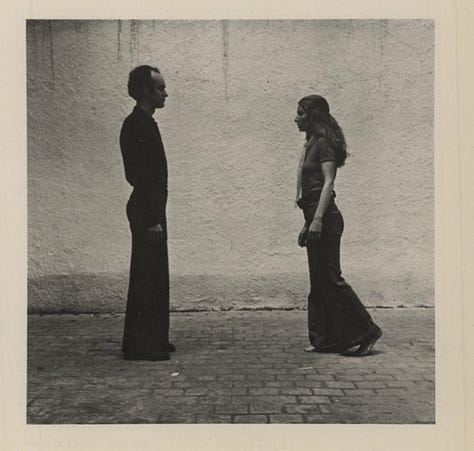

In 2015, the New York Times published a Modern Love essay called “To Fall in Love With Anyone, Do This.” In it, writer Mandy Len Catron describes a study by psychologist Arthur Aron that claims intimacy between two strangers can be accelerated by asking each other 36 questions.

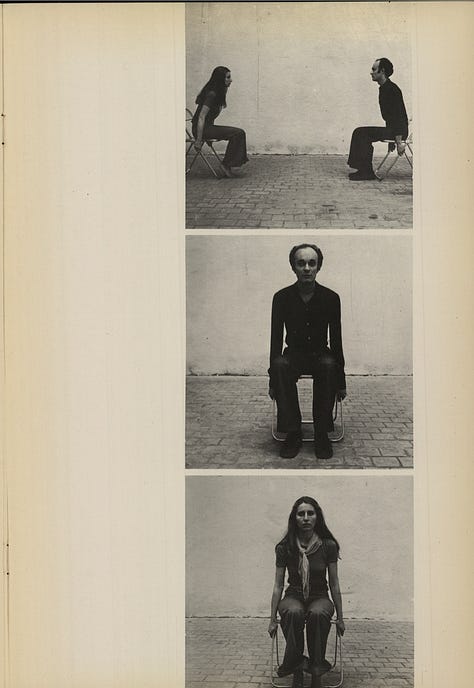

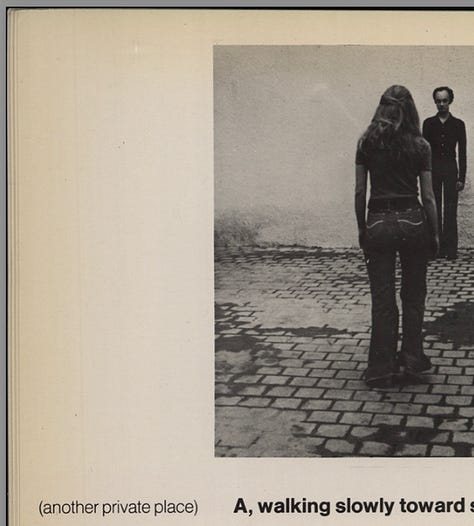

The essay begins on a first date, where Mandy tells her date the specifics of Aron’s experiment: a man and woman enter the lab through separate doors, sit face to face, and answer a series of questions.

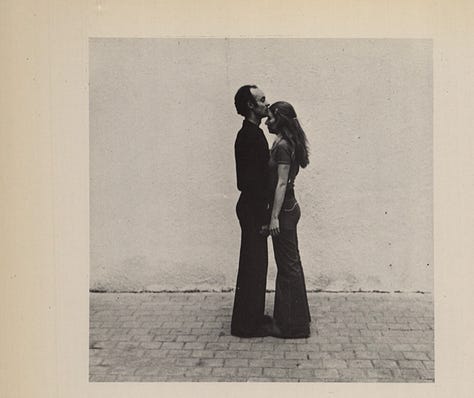

“…The most tantalizing detail: Six months later, two participants were married,” she writes. “They invited the entire lab to the ceremony.”

This intrigued her date, so over beers in a bar they cruised through all 36, finding out everything from the last time they cried to what they’d ask a fortune teller.

Daniel Jones, the Modern Love editor, said her essay blew the doors off the column, probably because readers saw in it a formula for falling in love. I was one of them.

I read it in an actual printed paper in Michigan. I kept it. And later that year, when I started dating someone, he found it in my nightstand. Soon we began answering one of the 36 each time we saw each other.

A few months in, he told me he loved me with the sheets pulled over his face, voice muffled like he was telling a secret. I should have said it back. I felt it. Instead I said, “But we haven’t finished the questions yet.”

He pulled the covers down, confused. “What?”

“We’re only at, like, 19.”

He laughed, but I wasn’t entirely joking. I clung to control, so a formula—if 36 questions, then love—was a comforting delusion when romance felt so enigmatic. Part of me believed I could earn it or prove I deserved love by answering all 36, as if intimacy were something I could complete once instead of something I had to practice forever.

x + y = ?

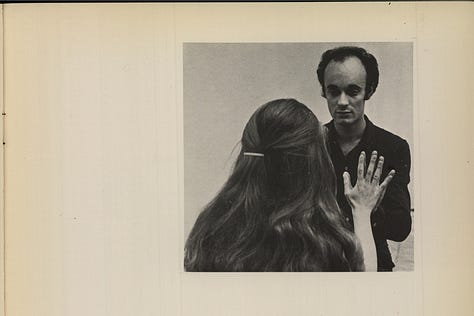

The questions are divided into three sets, each one more probing than the last. They lead to a level of conversational intimacy that’s difficult to manufacture without some sort of premise—be it a podcast mic, a tarot deck, a 12-step meeting, or a set of prompts. Containers like these give us enough time and space to be known.

When Mandy used it on her date, they didn’t instantly fall in love after answering the last one. It wasn’t until much later that they even began dating.

In 2025, a decade after her viral essay, she was in the paper again—this time in the vows section, announcing their marriage. When I saw that, I reread her original essay too. In it, she mentions that the questions that made her squirm most when she did them with her now husband, were the ones that ask you to give opinions about the other person, like 28: tell them what you like about them.

I'd had the same reaction when I did them. And few years into that relationship, when that question resurfaced in couples therapy. The therapist (a fan of Aron’s research) asked us to turn toward each other and say what we loved about the other. I cried hearing his answers.

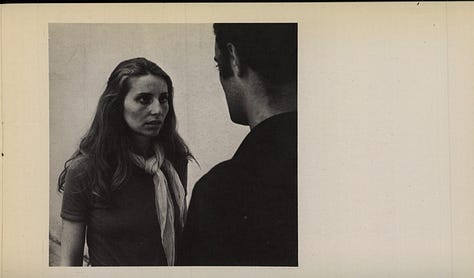

On the walk home, he said that seeing how hard his words hit me in her office made him realize he’d been distant. We got closer again, for a while. The questions gave us about six more months.

When we did eventually break up, I questioned the questions. Had they been a way to try to control the outcome—to fall in love, then to stay in it?

The first time I read Mandy’s essay, I was 24 and naïve enough to believe that lab-designed questions could guarantee lasting love. Perhaps they can, but love isn’t enough for a relationship to work.

I didn’t know how to seek solutions together when problems arose. I only knew how to handle things alone or run from friction entirely.

Whenever things got hard I’d go to the worst case scenario. “Why can’t you trust in a years-long relationship whenever there’s an issue?” he’d say. He was right. My fear of losing him was making me engineer certainty in a place that requires faith.

The harder I held on, the farther I pushed him away.

I was grasping onto the relationship so tightly that I did something so truly mortifying I’d blocked it out (my subconscious, doing me a solid for once) until I recently saw it in my Google Drive.

The Document 📑

I used a formula to fall in love, so to stay in it I made a blueprint to “fix” our relationship. A manual, as if he were IKEA furniture that came with instructions and an Allen wrench. Control had failed me—spectacularly—and yet somehow I thought a document trying to get ahead of any future problems could help. It was full of if‑then statements, earnest reminders to myself like this one:

If there’s an issue, listen to him! Don’t become overly apologetic or emotional

(then he ends up having to comfort you… when he was the one who came with the grievance). Don’t freeze or spiral, stay in your body. Ask questions. Try to understand, rather than be understood. Apologize. Do better next time.

The doc wasn’t necessarily the problem; the intention behind it was.

Oddly, Mandy had made a relationship document too. In a second Modern Love essay, called “To Stay in Love, Sign on the Dotted Line, she describes creating a “contract” with her partner—a written agreement about chores, sex, money, and expectations.The difference is that her contract wasn’t a desperate attempt to keep someone from leaving. It was an honest tool for two people who wanted to stay.

“It may sound calculating or unromantic, but every relationship is contractual,” Mandy writes. “We’re just making the terms more explicit.”

I’d missed this other essay when it came out in 2017, but only now am I able to grasp its thesis: love is less about luck or fate and more about being flexible enough to bend toward the other person without breaking yourself.

That sounds simple, but learning to relate might be one of the most difficult and valuable parts of being alive. And the particular ways relationships challenge each of us are wildly specific to our past.

For instance, Mandy lost her sense of self during a long relationship in her 20s. When they broke up, she discovered “...what it meant to fully inhabit my days and the spaciousness of my own mind.”

I, on the other hand, knew that spaciousness too well. I’d been so addicted to it there wasn’t room for anyone else. I wasn’t willing to trade my preferences for connection—and that’s what relationships are.

There’s a melancholy to the fact that we often learn and change as a result of relationships with people who will never experience us as the person they helped us become. Only the next one will.

The Fortress 🏰

I’d love to tell you that in the years since that break up, I’ve rewired my pattern and mastered the art of compromise. I have not.

I worry my impulse to hold tightly to my preferences has calcified with age—that the structures of my life are now fortress-strong. When I was younger, they were just scaffolding, and even then I struggled to let someone in. Will it be even harder now?

Mandy’s second essay—like her first—is nudging me on this exact issue. Our tendencies are opposite: she over‑identified with the other person; I refuse to let go of my own identity. But the solutions to change them are similar: tell the other person about our tendency and ask to treat it as a problem to solve with them, rather than one to hide from them.

This is uncomfortable. But if comfort is my goal, I should stay single forever.

Being alone is much easier—you never have to compromise, forgive, apologize—or most uncomfortable of all: lose. All relationships involve loss: of preferences, of time, of space. And eventually, loss of a person, whether death or choice does you part.

There’s no questionnaire or contract that can protect me from the grief that love guarantees.

Knowing it’s losable is why it’s so rich. It’s why we can’t stop talking about it, writing songs about it, making movies about it.

The Crack 🥚

Yesterday a friend showed me someone she wanted to set me up with. I did what I do best, began daydreaming about what it would be like if it worked out—so vivid I preemptively started mourning my mornings…my weirdly long walks getting shorter, my nights working on my computer until my eyes are blurry ending earlier, and all my secret single behaviors dissolving.

The routine-filled fortress around my gooey heart is costing me connection.

I want to knock it down, but I worry that I’ll miss being so in control of my time, my food, my apartment. But in Mandy’s second Modern Love essay, she seems to have found a Goldilocks approach that leaves room for each individual within the third thing: the relationship. She ends the essay writing:

“As I type this, Mark is out for a run and the dog is snoring at a volume that is inordinately sweet, and I am at home in the spaciousness of my own mind.”

That makes me believe I don’t have to choose between love and space. I can build a life with enough room for both: another person and my meandering mind.

So here’s question 1 of 36: “Given the choice of anyone in the world, whom would you want as a dinner guest?”

I’ll start, it’s you—the person who made it this far. Your turn, in the comments…

***

I don’t know the patron saint of this essay, Mandy Len Catron but I feel like I do because instead of pressing send on this earlier, I read her substack it in its entirety. She still writes about love and connection, and so much more, if you liked this Julie & Julia-esque issue, check her out, she seems like a very cool and smart person wise and is obviously a brilliant writer. I restacked some lines I particularly liked from what I read yesterday in note.

Thanks for reading this!

Listen, it’s my favorite holiday. (Well it was when I began this, I’m just slow, see here). I’ve talked about love here and break ups here and here:

so for this year’s February list… we’re doing the questions! I haven’t answered them since the story you just read, so I thought I’d take a stab at them, this time with you as my partner. Tell me if they “work,” and do a few in the comments. I’d love to fall in love with you too.

CAUTION MAY CAUSE L O V E

I did a few from each section, mostly lighter ones where the answers came quickly. I think lightness and ease is kinda what we all need right now.

Set I

3. Before making a telephone call, do you ever rehearse what you are going to say? Why?

If you’ve had a conversation with me… I’ve probably rehearsed it. I at least consider some talking points, follow-ups from the last conversation, things that would be fun or interesting to talk about if nothing comes up. I like to have those in my back pocket. I don’t know if this is part of being a good conversationalist or someone trying to control how I’m perceived?

5. When did you last sing to yourself? To someone else?

To myself. In the car. I love singing. I am terrible at singing.

6. If you were able to live to the age of 90 and retain either the mind or body of a 30-year-old for the last 60 years of your life, which would you want?

Body, because I am vain. But also because I think if I could move easily, my mind would be better? It’s hard for my current mind to conceptualize my mind being different in 30 years because my mind doesn’t feel much different from when I was 10 or 20. I feel like my mind has been my mind and therefore will be, maybe my 90-year-old mind will be a bit gentler?

9. For what in your life do you feel most grateful?

All the people I’ve met and shared moments with, however big or small.

10. If you could change anything about the way you were raised, what would it be?

Nothing because I wouldn’t be here now writing to you if it had gone any other way. Or maybe I would be and it would be a lot more articulate.

12. If you could wake up tomorrow having gained any one quality or ability, what would it be?

Able to play the guitar! Or to be a triple threat: sing, dance, act… (if that’s allowed as 1 ability?)

Set II

20. What does friendship mean to you?

Keeping each other inspired. Consistency of some sort. Make each other laugh. Hold our memories.

Set III

27. If you were going to become a close friend with your partner, please share what would be important for him or her to know.

Tell me 10 minutes before the time you actually want to meet and never tell me you did this.

35. Of all the people in your family, whose death would you find most disturbing? Why?

All my aunts and uncles. I must die before all of them go. It will be too hard to lose any of them. My parents, 2 cousins, and any of my friends. Ah acquaintances too, honestly I need to go before any of you go.

Thank you so much for reading it means a lot! Sorry if there are typos. keep in touch.

✷ THE LATEST PODCAST EPISODE ✷

**I put out a new episode this week:

Here are 2 relevant episodes from the archive below. Top one is only 14 minutes!!

Brilliant and beautiful as always. Thank you for sharing your heart with us. Also, what a trip down memory lane. I remember driving to an art opening in Culver City on a rainy night with friends and us discussing these 36 questions! WOW, feels like an eternity ago.

I consider my space, time, rest so sacred, I can’t imagine compromising these things for a partner or even a roommate. I need a partner who lives next door so I can have my own space. Lol

Definitely projector, only child, Pisces vibes. But I also know I need to work on eroding away my own rock solid fortress. 🙈

I also really identified with what you said about love being filled with loss. You get so much and lose so much all at the same time.

This might sound like a contradiction or projection, and if so throw it out: I wonder if it’s not so much a fear of losing your comforts as it is a fear of centering a man in your life when you’ve deliberately centered yourself / other women. In previous relationships/situationships, He was the force that guided so many of my decisions and it always felt like I was losing a piece of myself to be partnered. I fully believe this kind of loss is optional. We also don’t have enough examples of how to decenter men while being in romantic relationships with them, which makes this hard to imagine for most women to imagine. Someone I adore just made a YT video about this topic which is why it’s top of mind for me (no idea if I can share links here though).